King of Kings (1961) Revisited

I watched King of Kings (1961) on Easter Monday for the first time I what seems like a very long time. Whilst I've revisited certain clips in the intervening period it was good to take it in in it's entirety and on a large high definition screen, making those colours stand out all the more and doing justice to Ray's bold images and Jeffrey Hunter's blue eyes. Ray is perhaps best appreciated for his use of internal space and smaller' more intimate stories, so it's interesting that it's the big scenes that I most appreciate here.

One such scene, that has always been one of my favourites is the historical prologue, voiced by Orson Welles. Many recent films have highlighted the story's context of the Jews living under occupation by the Romans, but rarely to the extent here. Pompey's victory is effectively year nought for this story, everything beforehand is largely irrelevant and everything afterwards is related to it. Welles' narrative seamlessly moves from narrating Pompey's invasion and the subsequent skirmishes into directly quoting Luke's "historical" prologue to the nativity story as if they are cut from the same cloth. But of course Ray is essentially doing to his gospel what Luke has done to his - prefix it with historical gloss to give a sense of place, time and context.

It's disappointing, then, that this all gives way to such a conventional retelling of the nativity. Having seen this part of the story reworked and reinvented so many times, it's retelling here is entirely devoid of drama, except the slaughter of the innocents. Indeed it seems that Ray intends the main point of the first part of this story to focus on the violent context. Pompey's murder of the priests, the Romans' executions of insurrectionists, Herod's slaughter of the infants and finally Herod Antipas assisting his father's death literally kicking him off his perch. The narration links this all together with the unusual phrase "Herod self-crucified" linking him to both the executed revolutionaries before him and Jesus' inevitable crucifixion. Herod is an evil man, but in a sense he is just another person destroyed by the violence that accompanies the thundering machinery of a violent empire.

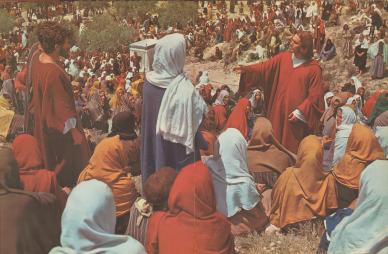

And herein lies the basis of Ray's gospel: Jesus is a messiah of peace that stands in opposition to all this power and violence. Perhaps this is why there is a such a preponderance of low angle shots in this film, stressing the towering magnitude of the Roman Empire and the lowly humble path Jesus and his followers will undertake. The camera often gazes up at the authorities in this film, but down on Jesus, most notably of course in that camera-attached-to-the-top-of-the-cross shot that is so very reminiscent of Dali's famous painting. That said there are exceptions in both directions: the Sermon on the Mount often captures Jesus from below, but when Salome asks Herod for John the Baptist's head, we get a high overhead God shot, a reminder that what goes on in the private quarters of the powerful and wealthy is still seen and judged by the god who sees everything.

However, this is one of the rare occasions where Ray uses some kind of filmmaking technique to force a supernatural interpretation of what we are seeing, perhaps because of the film's interest in power and the use of force. It's notable, for example, that we're treated to a very Markan baptism. There's no literal dove or protestations from John. Jesus may have heard a voice from Heaven, but we do not.

Furthermore, whilst several miracles are seen on screen, they don't use special effects. This isn't because the film is low budget, and I don't think it is necessarily to accommodate doubt, but rather that doing so would have forced a particular perspective. Lucius' reporting of other miracles is well documented, but note also how the resurrection is all off camera. I think it's significant that the only time a classic "special effect" is used, it's used by the devil during the temptation, and it's a lurid and unconvincing overlay of a tacky looking city. It's so jarringly out of kilter with the rest of the film's look and feel that it seems deliberate to me.

Jesus of course rejects Satan's advances, in fact the first words Jeffrey Hunter utters are "Man does not live by bread alone but by every word of God". Again given Ray's concerns with violence and social injustice this seems significant. Those opening scenes pit Zealots against Romans but sides with neither, because whilst Barabbas and the Zealots are concerned with earthy issues such as! presumably, "bread" Jesus emphasises that some things are more important.

As the film progresses, the idea persists that Barabbas's fighters are really just the opposite side of the coin to Roman violence. Jesus' way is radically different. It's interesting that every time there is a big set piece battle in the film, the kingdom of peace is shown going about its business in virtually the same space, but somehow in parallel to the warring Romans and Zealots. So in the opening overview whilst Rome defeats the Zealots Jesus is born. Later when Barabbas's men ambush Pilate's soldiers, the scene is prefaced by footage from just over the hill of John baptising his followers. And, of course, there is Jesus' alternative entry to Jerusalem via donkey which the Zealots attempt to turn into a revolution which ends in them quite literally being trampled into the dirt by the Roman army. There's perhaps a fourth example: in the background when Jesus is crucified there is, to borrow from Welles' opening narration, a sea of crosses - a sign that Roman violence has once again overcome Jewish violence.

The other notably unusual use of the camera that Ray utilises extensively in this film is the split-focus diopter lens. (This is a split lens allow one half of the camera to focus on a character in the extreme foreground whilst the other half focuses on a character or object in the background). Despite my familiarity with this film it was a surprise to see it used to widely given that it's a technique largely associated with the seventies. It's used significantly in All the President's Men and on YouTube there are demonstrations of Brian DePalma's repeated use of it in Blow Out. But this was 1961 which makes Ray very much a leader in this field. In high definition there's at least one shot that is useful for demonstrating the technique. After the Sermon on the Mount Jesus and Peter talk and if you look at the tree that runs diagonally across the scene you can see how it moves from being blurred on Jesus' side to being in focus next to Jesus.

There are a few other nice camera moments that I had not noticed before. There were a couple of nice compositions I really appreciated this time around. The one at the top of this post is from the Sermon on the Mount, the one lower down is from Jesus' trial. Also between Jesus' arrest and his subsequent death there's quite a bit of footage of Judas including one where he somehow gets literal blood on his hands and another where he witnesses the crucifixion up close and picks up a stone (this doesn't seem coincidental so it's perhaps a reference to the earlier non-stoning of the woman taken in adultery scene).

Another character who gets developed in ways beyond their character's development in the Bible is Pilate's wife. Firstly she is involved in discussions that it seems highly unlikely that Pilate's real wife would ever have been. But, in contrast to her waspish, jaded and cynical husband, she is consistently intrigued by Jesus, his message and the stories that surround him. It's stressed that she is Caesar's daughter but she sneaks out with Lucius to witness the Sermon on the Mount. There's a moment of reflection by a pool of water, and most significantly she is present on Jesus' road to the cross. Indeed when he stumbles she even steps forward as if to offer to carry the cross. All this seems in keeping with the moment in Matthew when she warns Pilate of the potential consequences of killing Jesus, but unusually this moment is not present in the film. The film was much cut and perhaps this is a moment that was filmed but ultimately left on the editing room floor.

I think the same fate must have accompanied some of the footage of Mary Magdalene. She is present in early scenes, most notably when she pops in for a chat with Jesus' mother, but then she disappears from the film right up until it's time for her to witness the resurrection.

However, the main omission that most Jesus films include is the presence of the Jewish authorities. This isn't just about edits in post-production, it's far more significant. Caiaphas is one of Herod and Pilate's cronies, but there are no other Jewish official leaders to speak of, nor are there any Pharisees. Indeed, aside from Caiaphas and Barabbas's dismissal of his significance there is no real opposition at all to Jesus and his message from within Judaism. Jesus trial in from of Caiaphas is given the briefest mention, but the soldiers who arrested him are Roman. Given how many Jesus films have been labelled anti-Semitic, this film goes to considerable lengths to distance itself from any such accusations fitting for a version of the Jesus story that goes to such lengths to portray him as the antidote to violence.

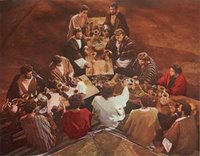

Lastly, there is the Great Commission scene on the beach, clearly in Galilee rather than Jerusalem and on the flat rather than on a mountain. Interestingly, immediately after Jesus words the disciples split up and head off in different directions. According to Acts of course, the church clung together in Jerusalem for several years before really splitting up to travel further afield, but it' say nice visualisation of their future. As a big fan of Rossellini's 1950 film Francesco, giullare di Dio (Francis, God's Jester) I can't help wondering if this is a nod to the final scene in that film where Francis' followers spin round until they fall over and then head off in the direction they are pointing. Jesus' method of commissioning may be more serious, but it's message no less important, for those living under Roman rule, for those in 1961 and for us today.

Labels: King of Kings